Dear Liz (ha!),

If I understand your point correctly, it’s a good one: what is the relationship between metaphysics (or, as I often think of it, psychological theory) and practical philosophy? Let me bounce some ideas off you.

For some people, the big questions about life – Is there a God? Why are we here? – can be a distraction from daily living. In extreme cases the search for answers, and the failure to find them, can lead to anxiety, depression and dysfunction. Browning was being ironic when he wrote, “God’s in his Heaven—all’s right with the world!”, but the words reflect that, for many people, the idea of the existence of a God who has all the answers, even if He doesn’t fully reveal them, can be comforting enough for them to get on with their lives with peace of mind. In this way, the metaphysics—whatever they are, however they work—can be a way of quarantining the quotidian mind from disturbing thoughts.

Esse…provides a metaphysical answer that takes us beyond the traditional idea of God

So, to my way of thinking, the relationship between metaphysics and practical philosophy is that they are separate but symbiotic (it’s a two-way street: people need a metaphysical construct to help them get on with their daily lives, and the search for meaning gives effect to metaphysics).

Esse, to me, provides a metaphysical answer that takes us beyond the traditional idea of God to one that is secular (and, strictly speaking, atheistic—i.e., non-theistic), rational and humane. It’s something that I think the modern mind can accept, and then get on about applying itself to life.

But this is really looking at the relationship between Esse and day-to-day life from a theoretical perspective; what are the practical implications?

God and the World

I’m going to try to answer this by referencing Christianity, as it’s the religion we both know. In Christianity, God and the practical world are intimately connected. God is the metaphysical solution (creator of heaven and earth, with a plan for humankind) who is also involved in human affairs (showing the Hebrews the way to the promised land, making a gift of his son to the world). The West repaid the compliment by adopting Christianity as the religion of empires and nation states. The relationship between God and Man was engaged via the Church which, in turn, had an ambivalent but usually mutually supportive relationship with the State. That changed over time with the Protestant Reformation and the rise of non-conformism, both of which put more emphasis on the relationship between God and the individual. Christian Puritanism appears to have given particularly robust expression to the idea of God’s will working through the day-to-day lives of ordinary people.

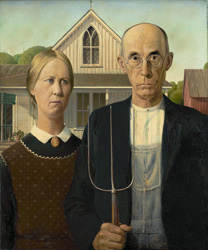

Christian Puritans: a robust expression

That’s the potted history, as I understand it. Now let me share with you how I see this relationship in terms of my own experience, beginning with a brief look at my childhood and later years (sorry to bore you, but please stay with me…).

God and the Individual: a Personal View

I was brought up as a Wesleyan Methodist, in which the sincerity of one’s relationship with God was front and centre—even more so (I would argue) than God or Jesus Christ themselves. The temptation to egoism was obvious. When I lost my faith, as one does, at the age of seventeen, the shallowness of my relationship with God was revealed to me in the most shocking way. It was easy for me from that point onwards to believe, aggressively, in nothing.

So that relationship failed, to be replaced in later life by a less personal, more institutionalised, brand of Christianity in the form of Anglicanism. The terms in which it expressed the relationship between God and the congregation—through pre- and post-Reformation traditions, the historic role of the Church of England in building the nation state and subsequent empire, the centrality of Christ the Redeemer, the effect of ritual in enhancing the sense of communion, and the practical and symbolic functionality of the Book of Common Prayer—were much more congenial to me.

What really attracted me to Anglicanism, however, was the way it presented the psychologically powerful idea that, through God’s unconditional love for humanity and Christ’s sacrifice, the “penitent” (receptive) spirit[1] can be rescued from alienation into a feeling of belonging. That worked for me: the beauty and the power of the idea—quite independently of any consideration of the existence of God, or whether the interpretation of Christ’s death was historically accurate, or whether Christ really rose from the dead—helped me to see beyond my own alienation to a relationship in which I was accepted, warts and all.[2]

Escape from prison/release from alienation

It is the idea, which for all I know might be entirely human in origin, that works for me, and not the supernatural apparatus associated with it. It remains, for me, affective and therapeutic, and is the reason why I continue to identify as Christian.

This acceptance of the psychological benefits of Christianity minus the supernatural trappings might properly be regarded as “cultural Christianity”—and that’s where I think I’m heading in describing the relationship between metaphysics and life at a practical day-to-day level.

The Individual and the Good Life

In this theoretical model, Esse is a self-contained metaphysical solution with no affiliation to any religion, and Christianity is regarded as a strictly cultural phenomenon with powerful and humane psychological benefits.[3] The two are quite separate. Both impinge on the life of a thinking individual, however, and I believe they can do so positively, with Esse satisfying the intellectual curiosity about first causes and destiny, and a cultural version of religion (Christianity, in my case) providing the spiritual richness and moral grounding necessary for a good life.

But let’s drill deeper: how does the model play out for the individual who is looking to create a life for himself/herself, and wondering how to fill the hours in each day in a way that will help, eventually, to achieve that goal?

As an existentialist, I’m reluctant to be prescriptive about this: we all must decide who or what we want to “be” (hence the deliberate vagueness with which I wrote about “life” and “goal” in the preceding paragraph). For this reason, I’m going to refer again to my own experience as I try to formulate an answer (still awake?).

As I think about it, I realise that I need to go back beyond my own experience to that of the people who shaped me—my family. The two sides of my family were quite different: Methodist and quietist on my mother’s side, Baptist (or was it Congregationalist? Or Presbyterian, even?) and socially active on my father’s. When I think of them as models for my own choices and behaviour, I lean towards my father’s side, because the people on it were more dynamic and outgoing and had a real, positive impact on those who knew them.

My father’s aunt and uncle were teachers who worked during the 1930s Depression in a particularly disadvantaged area of Britain[4], where children would turn up to school each day unwashed and in the same clothes minus shoes (their parents couldn’t afford them) and hungry (their parents couldn’t afford food). My great aunt and her sister (my paternal grandmother) started a soup kitchen and joined the Labour Party. My great uncle joined too, and nearly became a Member of Parliament. Perhaps his greatest political achievement was to prevent the Communist Party from establishing a foothold in that part of the country.

Only Hollywood would ever think of building a coal mine at the top of a hill

The sense of justice that motivated them owed at least as much to their religious beliefs as to their political ideology (as well as their own personal decency). They were boots-and-all believers for whom God was a moral, driving force. I don’t share their idea of God but I admire them and what they did and I share a lot of their values. I aspire to be like them, although there’s nothing religious in my motivation, just a sense that doing good with integrity and conviction is a worthy way to live.

Pluralistic, but Coherent

In summary, I see the relationship between metaphysics and practical philosophy as pluralistic, consisting of three separate and independent elements—God-as-existence/Esse (metaphysics), a “cultural” version of a religion (a form of spiritual epistemology) and behaviour modelled on exemplars from one’s personal background or tradition (ethics). Because of their separateness these various elements must be applied sequentially rather than holistically, but I think they can still add up to a coherent perspective on life.

Thoughts?

Cheers,

Stranger

[1] The penitence being symbolised by, and enacted on behalf of all people through, Christ’s sacrifice.

[2] In my state of mind at the time, the idea—which I assume to be human in origin and the work of a genius—restored my faith in humanity.

[3] The role of creativity in the individual’s engagement with religion and pursuit and attainment of grace is an important concept in Esse which merits separate consideration rather than a partial discussion here.

[4] The Rhondda Valley, South Wales—an important coal mining centre at the time.

Pics

- American Gothic, by Grant Wood

- St Peter Released from Prison, by Gerrit von Honthorst (1592-1656)

- Still from How Green Was My Valley (1941), 20th Century Fox