One way to think about Byron Bay is as a sort of bohemian Cote d’Azur: many of the rich who retire or build holiday homes here made their money in the more louche areas of capitalism, such as media or entertainment, and its style and atmosphere come from the young and partly transient population of surfers, neo-hippies, buskers, artisan pop-up stallholders and tattooed baristas.

The vibe is laidback, rhythmic, sensuous (all those colours, sounds, smells and flavours) and sensual (tanned young bodies and…but enough of that).

Like its Mediterranean counterpart, it has natural beauty to spare: the town prostrates itself behind an elegant sweep of sand that curls at one end into the easternmost point of Australia, Cape Byron, before losing all sense of itself in the almost fluorescently blue ocean.

Good morning, Australia (Source: west1.com.au)

You don’t have to be rich to live comfortably here, and it doesn’t matter how old you are, because it’s a place for the young at heart. And if you’re not, you soon will be. After all, the sun makes its first mainland-Australia landfall here every day. Who can contemplate that fact without feeling, somewhere in their bones, a stirring of youthful optimism?

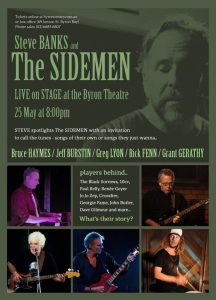

It’s home to a lot of artists and musicians, including most of The Sidemen, which helps to explain why they launched here. But don’t let their residency beguile you into thinking they personify the town’s insouciant hipness. When I say they “launched”, I mean “went off like a rocket”.

Picture the scene: Byron Theatre, a charming weatherboard structure in the middle of town, on a balmy Saturday evening in May. The 246-seat auditorium is sold out and the audience—mainly boomers like myself with a smattering of Generations X and Y and the occasional iconic Byron yummy mummy in designer hippy gear—is good humoured and, between sips of wine or beer, talkative as it waits for the show to begin.

We’re here to see five musicians who have spent their careers backing some of the biggest names in rock or pop since the 1960s but who, until tonight, have never appeared as an act in their own right.

Jeff Burstin and Rick Fenn (guitars), Bruce Haymes (keyboards), Greg Lyon (bass) and Grant Gerathy (drums) have worked variously with the Black Sorrows, Jo Jo Zep and the Falcons, 10cc, Nick Mason and Dave Gilmour (both of Pink Floyd), Renee Geyer, Paul Kelly, Peter Green (Fleetwood Mac), Crossfire, Georgie Fame, the John Butler Trio and…that will do for now.

Roll up! (As in, come and see the show…)

The project is the brainchild of Steve Banks (Banksie), a gifted singer, songwriter and guitarist (and, full disclosure, old mate) who, only a few years ago, escaped from the world of business in Sydney and relocated to Byron to pursue his long-held and much-deferred musical dreams.

His aim (which, it turns out, is part of a wider agenda) is to give these massively credentialled and seasoned musicians the opportunity to play live together and entertain the audience with stories about their times on the road. It’s an irresistible formula.

It also raises some interesting questions. The show is formally billed as “Steve Banks and The Sidemen”. How will Banksie balance his role as vocalist and front man with his avowed intention of putting The Sidemen “front and centre”, given that they are functioning, to all intents and purposes, as his sidemen?

And what is the audience hoping to gain? A trip down memory lane? A chance to revisit the soundtrack of their lives? Relive the glory of their youth? Experience once again the glamour of the stars they once worshipped? Enjoy a bit of celebrity gossip?

Paradoxes and ambiguities, I think. But not for long: the evening will end by resolving itself in, for me, a moment of unexpected clarity.

THE SOUNDTRACK OF OUR LIVES

As far as this audience member is concerned, the answers to all the above questions are in the affirmative. I’m a tailender of the boomer generation: the music and the acts that The Sidemen brought to life and nurtured for all those years—still nurture—helped shape my sense of myself and my view of the world. I’m pretty sure all my peers in the auditorium feel the same way.

Let’s take a few random examples. Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames. I grew up in the UK but never saw them live. They were, however, a frequent, vibrant presence on our grainy black and white TV, with Fame on Hammond organ backed by a very tight r’n’b/jazz/ska combo (bands like that were always “combos”, they were never “bands”).

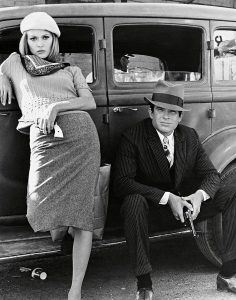

He had only three top 10 hits, but they all went to number one. My favourite was ‘Yeh Yeh’; the one I remember best, ‘The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde’, was a tie-in with the 1967 movie starring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty. With the latter, Fame became the epicentre of a cultural moment: the film launched a style revolution, with Dunaway’s elegant gangster-gal costumes single-handedly killing off the mini skirt in favour of the midi (much to the disappointment of my 13-year-old self).

Gangster gal (Source: Warner Bros)

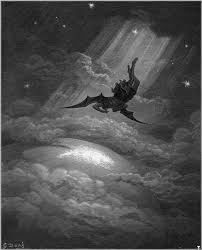

Pink Floyd. This is a band you never speak of in just the past tense: they were, are and forever will be. One of the reasons they will endure, in my view, is that, while they charted the outer reaches of psychedelia, their far-outness was perhaps one of the most reassuring things about them; what was really unnerving about Floyd was their connectedness to reality.

We all know the sad story of sweet Syd Barrett. He defined Floyd’s originality as a combination of eccentric English pop sensibility (‘See Emily Play’) and space-age or science-fiction themes and imagery (‘Astronomy Domine’). It was after Syd had left the band and become institutionalised that a dark psychosis entered the music, culminating in the monumental and classic Dark Side of the Moon. But the strength of the album, I would argue, lies in the fact that its edginess is grounded in the stark contemporary realities of the Nixon years, Watergate and the Vietnam War.

There’s more to Floyd than this, I know, but we’re talking about how music shapes lives and memories. I was introduced to Dark Side by a friend from school (let’s call him Malcolm) who had dropped out after Year 10 and fallen under the spell of dope, acid and an all-consuming existential rage. We no longer had much in common personally, but we rediscovered each other through that album. I discovered a lot about myself, too, and I was grateful for the fact that, while the realism at the album’s core would take me close to the edge, the sheer artistry of it would lift me up and set me down somewhere safely again.

Coming down after listening to “Dark Side”

It didn’t work out that way for Malcolm. The last I heard about him (and this was only 10 years ago), he had become the town’s tragic freak, standing on street corners, cross-dressed and stoned, yelling at passers-by. He lived alone in sheltered accommodation. One night the police turned up, took him away, and that’s the last any of our mutual acquaintances saw of him.

If Floyd defined the downside of my adolescence, 10cc was very much part of the upside. Apart from the Beatles and Beach Boys, few bands, in my opinion, have so consistently raised pop to the level of art (and I don’t mean pop-art). ‘Rubber Bullets’, ‘The Dean, His Daughter and Me’ and ‘Wall Street Shuffle’ were part of the soundtrack to my later school years, while ‘I’m Not in Love’ came out while I was at university. It was hard to know where pop would go after that; perhaps it’s one of the reasons punk rock became necessary—after all, the song has become deeply embedded in the sonic wallpaper of every shopping mall in the Western world. Everything about it is perfect—not least the multi-vocal backing track which, along with the overall Spector-ish ambience, takes me back to The Mindbenders’ 1965 hit, ‘Groovy Kind of Love’. Eric Stewart sang vocals on both records. I hadn’t realised it until now, but that guy bookends my life from puberty to early adulthood.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” says a familiar voice over the PA, “pray silence while The Sidemen take the stage and reserve your applause for when I come out to join them.”

The audience laughs. So that’s how he’s squaring the “Sidemen front and centre” circle. Classic Banksie.

LICKS AND YARNS

First number, and they set the tone perfectly with a mid-tempo disco beat that turns out to be the 1981 Darryl Hall and John Oates hit, ‘I Can’t Go for That’. All we know at this point is that The Sidemen will be playing songs they used to play, wrote or wished they’d written. Presumably this number, penned by Hall and Oates, falls into the last category. Which kind of makes sense as It’s stylish and accessible—a bit like The Sidemen themselves.

Right to left, we have Jeff, head to toe in black, former lead guitarist with the Black Sorrows and Jo Jo Zep, playing a custom-made Noyce, also black, through what can only be described as a rather phenomenal-looking-and-sounding Fender amp in a matching black cabinet offset at the front by the tastefully subdued glitter of a silvery grill cloth.

(This amp, as will become apparent, is crucial to the whole enterprise.)

Greg, his head crowned with a magnesium halo of curls, is easily the most exotic-looking, but substance more than matches style as he rolls out a bass line that’s solid and vibrant, like a hardwood timber floor.

Grant on drums is in his early forties, which makes him the baby of the group but, judging by his relaxed composure, he could be the most experienced of them all.

Rick, tall and English, coaxes perfection out of a Roger Giffin Strat copy with a gentlemanly charm that makes the whole thing look so damned easy.

And Bruce, far left, sitting ramrod straight at a Nord keyboard, adds colour, texture, depth and rhythmic nuance with a poise that totally belies his self-effacing personal manner.

Let it rock (Source: LisaGPhotography)

Behind Jeff, a bonus for the evening—backing singers Vanessa and Martine; and, front and centre, singing his heart out and grinning like a kid in a toy shop, Banksie.

Jeff is the first to receive the This Is Your Life treatment. Born in Mt Waverley, Victoria, to a musical family, he played in several bands before international success with Jo Jo Zep. Later, as part of the Black Sorrows, he co-produced several platinum-selling records with Joe Camilleri.

“Name one of the highlights of your time with the Sorrows,” says Banksie.

“Playing on the steps of the Sydney Opera House.”

Greg pipes up from the back: “I was there!”

Jeff turns: “Were you?”

These guys have so much history to share, they’re still discovering each other’s, on stage, in real time.

Cue two Sorrows numbers, ‘Hold on To Me’, with its killer opening line (“We were dead on arrival…”), and ‘Harley and Rose’.

Next up: Grant. Born and grew up in Sydney (Maroubra/Matraville) and moved to Byron because “the surf’s better”. A nun taught him piano as a kid: “it was horrible”. As a drummer he’s worked with Labi Siffre and Jackie Orszaczky among others and toured the world with John Butler, playing major venues like Madison Square Garden.

This leads into Siffre’s ‘I Got the Blues’—which I initially mistook (similar intro) for Butler’s ‘Zebra’.

Greg Lyon was originally from Melbourne (where Jeff and Bruce are still based). He started gigging in his teens with someone called Little Johnny Farnham and became a regular in the Aussie Blue Flames, the local combo which backed Georgie Fame on his Australian tours. After a spell in the States he relocated to Byron, combining music with a 20-year career in academia, during which he helped create Australia’s first contemporary music degree course at Southern Cross University.

They play ‘Yeh Yeh’ which makes my night. It’s at this point that I notice that the audience, just like me, are seriously enjoying themselves.

And then it’s Greg’s turn to do an intro.

“Not so long ago, Rick mentioned to me that, with Mike Oldfield, he’d co-written a song for Hall and Oates, ‘Family Man’, which enabled him to buy a house in Byron Bay.” A mercenary glint lights up his eyes. “So naturally I said to him, ‘Let’s write a song together’. This is it.”

It’s called ‘Do I What I Say, Not What I Do’. Greg apologises for the “indulgence” and says that it’s still a work in progress. No apology necessary, of course; the song rocks along very nicely.

Rick’s next. Born and bred in Oxford, England, his big break came in 1976 when the drummer of 10cc recommended him to the rest of the band. He joined to promote the Deceptive Bends album and has been with them ever since. Along the way he recorded an album with Nick Mason from which a single, ‘Lie for a Lie’, sung by Dave Gilmour with Maggie Reilly on backing vocal, was a hit in the US. And, with Pete Howarth of The Hollies, he wrote a rock opera, ‘Robin Prince of Sherwood’, which toured the UK and had a good run in the West End.

The band launches into ‘Lie for a Lie’ followed by ‘Dreadlock Holiday’, Grant nailing down reggae snare fills in a way that makes any distinction between technique and feel totally meaningless.

Suddenly it’s the interval. How did that happen?

A HARSH REALITY

The first I knew for certain that the gig was taking place was when Banksie rang me.

“Listen, mate, I got a favour to ask. Equipment hire is pretty expensive and I’m trying to keep costs down so that there’s as much money as possible for the band. Could I possibly borrow your amp for Jeff to use? We’ll need it for a couple of weeks, to cover rehearsals as well as the gig.”

Let me get this straight, I thought. Jeff Burstin, ex Jo Jo Zep and the Sorrows and ARIA Hall of Famer, would like to borrow my lil’ old Fender Hot Rod amp which, because I’m still a 10-hours-a-day desk-bound working stiff, I hardly ever get to use?

Two possible replies sprang to mind: “Is the Pope…?” and “Does a bear…?”.

Is he? Does it? (Source: eyeofthetiber.com)

Eventually I settled for, “Yeah, sure, no worries”, and hoped it sounded nonchalant.

Yes, I admit, for a moment there I was reduced to a state of childish excitement. My amp? On stage with these guys? But I make no apologies.

We all have our passions—music, sport, politics or whatever—and our heroes in those fields. Mine from an early age were guitar music, guitarists and their guitars: Eddie Cochran and his Gretsch, Bert Weedon and his Guild, Hank Marvin and his Burns, Lennon and his Rickenbacker.

Most of us don’t have the talent to indulge our passions personally, at least not at an elite level, and therefore do so vicariously, through our heroes. So, on the odd occasion when our personal lives and the idealised world of our heroes intersect, it’s OK in my book to be, as I was, a little star-struck.

But the sense of referred glamour didn’t last long, because Banksie’s request reflected a harsh reality: the economics of making and performing music in the 21st century.

Musicians have always been the last to get paid, but it’s even harder for them today. The internet, social media and streaming services have destroyed the business model of record sales, regular gigging and tours that underpinned the music industry’s growth in the 1960s and 1970s.

Online technology has made music more ubiquitous than ever, especially through personal listening devices, so that individuals these days are increasingly accessing music privately and relying less than their parents did on mass media and live venues.

The alienating effect of personal listening devices… (Source: everydayisspecial.blogspot.com)

And advances in electronic music equipment have made it easier for solo performers, DJs or small groups to flood venues with big digital soundscapes at a fraction of the cost that promoters would have to pay to hire a more traditional band of three, four or more musicians.

It’s got to the point that many live venues don’t charge the punters for the music. The idea is that the band brings in the crowds to increase the trade at the bar, then gets paid out of the “additional” takings. The proportion they receive is usually no more than a few hundred bucks in total.

I’ve even heard that some venues expect the musicians to underwrite the bar take: so, if the expected “additional” $2,000 or whatever doesn’t materialise on the night, the musicians are expected to compensate the venue. You couldn’t make it up.

My guess is that, for most of their working lives, The Sidemen would have followed the traditional template of gigging, session work, song writing and teaching, enabling them to enjoy satisfying careers and decent, though probably not particularly flashy, lifestyles.

Now, they face the same challenges as everybody else.

“When you think of all the talent and experience and years of musical history that these guys represent, there’s got to be a way of rewarding them more appropriately, in a way that gives value to the public too,” said Banksie toward the end of the call. “The question is, what is it?”

He was speaking now, not as the stars-in-his-eyes front man planning a major gig, but as a successful, retired businessman warming to a new challenge: how to introduce a measure of equitability in an industry where, more than ever, producers and creators are being denied a fair share of their rewards by distributors and consumers.

“I don’t know,” he said, answering his own question, “but I’m working on it.”

SHARING A PERFECT WAVE

I confess I’ve never seen the 2001 Australian hit movie, Lantana. Noirish, introspective stories about tangled relationships in suburban Sydney are not my thing. As far as I can tell, though, the title and creeping-plant imagery are well suited to the theme. I just tried reading the plot summary on Wikipedia; it was like ingesting broken glass.

Cue Bruce. He was part of the team, including Paul Kelly, that created the film’s soundtrack. The second set begins with the Lantana trailer, minus sound, playing on the backdrop and Bruce improvising over it. A dark and empty road lights up like foil in the headlights of a car; couples couple or glare moodily at each other; one woman talks tearfully to another; two men snarl at each other; Geoffrey Rush stares down at the Hawkesbury River, as into a metaphysical void; a woman’s body is thrown from the car….

Bruce’s music creeps from the shadows and curls itself around the images like the caress of a lover which, at any second, could snap into a stranglehold.

He’s from Bright, a charming old gold mining town in Victoria. Before being discovered by Richard Clapton’s bass player, he’d never played to an audience of more than about five people. Now his track record includes working with Kelly, Russell Morris, Renee Geyer, Colin Hay, The Waifs, Archie Roach and many more. He’s worked on the music for 15 films and won an ARIA for Lantana.

“You were there when Kelly wrote ‘How to Make Gravy’, weren’t you?” asks Banksie. “What happened?”

“Well, he walked into the room, playing a guitar, and said, ‘What do you think? It’s got a few chords from another song so I’m not really sure….’ And I said, ‘Nah, it’s really good. Work on it.’”

From little things, big things grow.

Guest vocalist Mark Jelfs channels Kelly with a near-perfect rendering of ‘Gravy’, and the show changes gear. The interviews are done, and the songs are no longer in support of anecdote or historical perspective. From this point on, The Sidemen are playing whatever the hell they want to.

The classics—so many of them my personal favourites—come thick and fast: ‘Rag Mama Rag’, ‘Drive My Car’, ‘Come Together’, ‘Heading in the Right Direction’ (the Renee Geyer classic with Vanessa delivering a beautifully judged lead vocal), ‘Shape I’m In’, ‘Oh Well’ and ‘Family Man’.

People are dancing, filling the space in front of the stage; the rest of us are either standing or rocking in our seats, clapping time. I turn to my Better Half: “Hey, that’s my amp up there!!”

One timeless moment (Source: LisaGPhotography)

“Yes, dear, lovely,” she says, and pats my knee before losing herself in the moment again.

We’re all reliving the best musical times of our lives, but there’s something else going on here, too. It’s particularly noticeable on ‘Come Together’ and an unrehearsed ‘Sunshine of Your Love’ which forms part of the encore (Rick walks over to Banksie: “Is this in E?” Banksie laughs and nods.)

Is it the sound quality? It’s been good all night, but now it seems to lift a notch. Or maybe the songs are taking on a new, fresh life of their own. We know them inside out, but they sound clear and pristine, as though we’re hearing them for the first time.

The Sidemen are not just purveying musical history, they’re creating their own timeless moment—and we’re part of it.

That’s not just my opinion. It’s clear from the mood of the rest of the audience as we spill out onto the street that it’s been a pretty special evening. So often when you get carried along by a crowd you feel as though you’re spiralling downward into something; not this time. The sense of energy and release is palpable, as though we’re all surfing the same perfect wave.

That’s when my moment of clarity hits: the real story of The Sidemen is not about the stars they supported back in the day, but about the talent, skills, hard work, creative energy and unassuming professionalism they’ve brought, and continue to bring, to every job they’ve done.

And it’s about the enduring musical legacy and tradition they’ve created in the process. Stars come and go, but it’s the side men and women of this world who keep the show on the road.

Job done (Source: LisaGPhotography)

At the pub the next day we catch up with Banksie, his family and friends, and most of The Sidemen. The mood is tired but happy. Bruce has had to go back to Melbourne for a gig. Before he went, he said something to Banksie which, we agree, will resonate with us for a long time.

“In 40 years of playing live, that’s the first time I’ve ever spoken on stage.”